21 tools to document your Python project

Overview of tools and services to document your Python web application from installation instructions to public API. How to make sure API documentation is in sync with your code. How to serve internal documentation and keep it private.

Why documentation matters

One of the best questions you can ask a team before joining it, is whether it has any documentation. Just as dirty bathrooms in restaurants suggest a dirty kitchen, poor documentation in software companies suggests rusty software design and poor processes.

Below, I will share what I know about the tools for creating API and project documentation. I will not touch on the questions of processes; it’s a separate topic. Here, only tools and services. My default context for a project is a web project exposing an HTTP API and likely written in Python.

API documentation

No matter whether the API is public or private, it needs to be documented. We have several options on the plate.

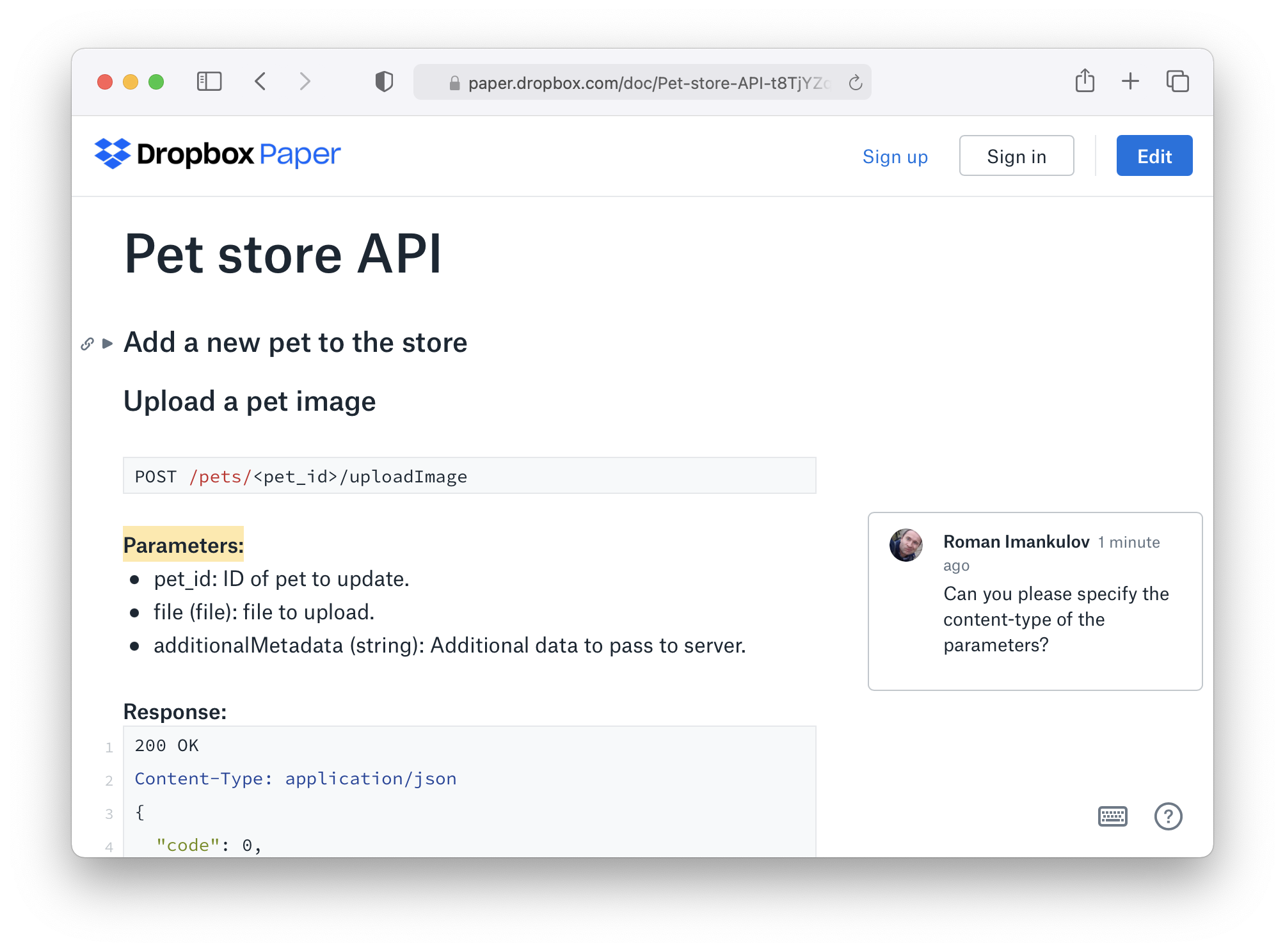

Dropbox Paper or Google Docs. The most straightforward approach is to write all the docs manually. At Doist, we used Dropbox Papers for API drafts and shared them across the team. The advantage of this approach is that you can API-first without any code yet, iterate quickly, don’t need to install anything or convert between the formats, and can quickly gather the feedback in-place.

On the flip side, this approach gets unwieldy quite fast. You end up with multiple Dropbox papers lying around with different formats, and besides, these documents get out of sync with the actual API quite fast. While convenient, I wouldn’t recommend Dropbox Paper or Google Docs for anything but the draft versions of the API.

API draft in a Dropbox Paper

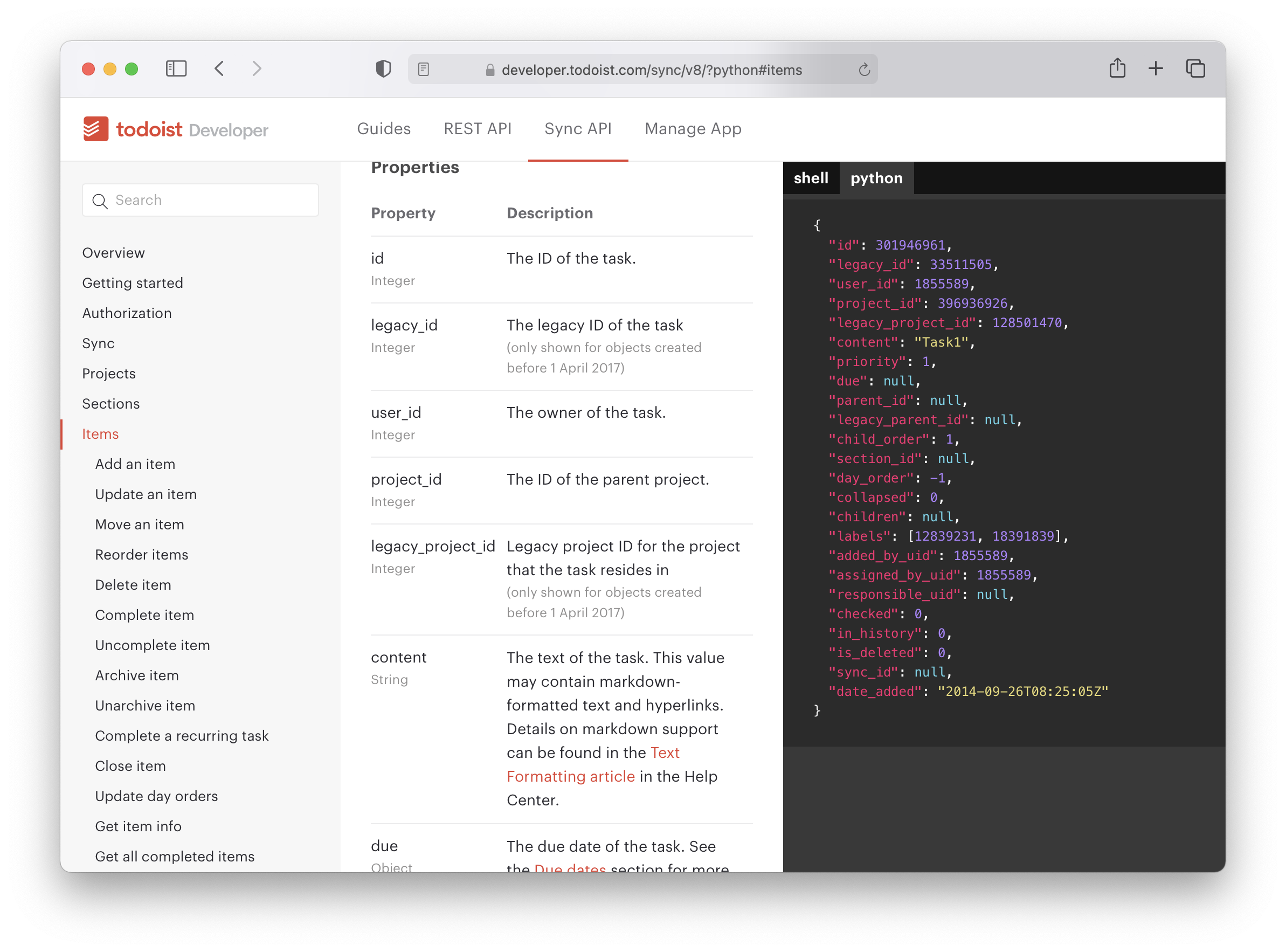

Slate and friends. The next step towards a more controlled evolution of the API documentation is a tool like Slate and the API documentation in git. It’s still text that you need to write manually in Markdown, but Slate provides a structure, a slick renderer, and lets you publish your API as an independent website.

Todoist API documentation is made with Slate

One problem with Slate is that it couples the code, the UI, and your documentation in a single repository. Their way of installing the tool is cloning the entire repo and replacing their sample content with yours. There is no simple way to upgrade your application to the new version of the API. You can clone again and copy your files if your changes are only on the documentation side, but if you find yourself tweaking the UI, the upgrade becomes more challenging.

Another problem, and arguably, a much bigger one, is that it takes significant efforts and diligence to keep the documentation and the actual API in sync. If someone adds a new field to the object, they need to remember to update the documentation accordingly. With Slate, there’s not much you can do beyond remembering, but later we’ll see how we can address this issue by generating documentation from the code.

OpenAPI specification

Who cares about WYSIWYG editors or markdown when you write YAML! Everybody loves YAML, and the OpenAPI ecosystem lets you take advantage of your passion. Let’s talk more about OpenAPI and what it brings to the table.

Everybody loves yaml. Source

OpenAPI in 2021 should be considered the de-facto standard for API specification language. The #1 reason to adhere to OpenAPI, beyond pure love for YAML, is the tooling that lets you write, validate, test, mock, and document your API, render it with a website, generate API specifications from code, and generate API clients from specifications.

OpenAPI editors

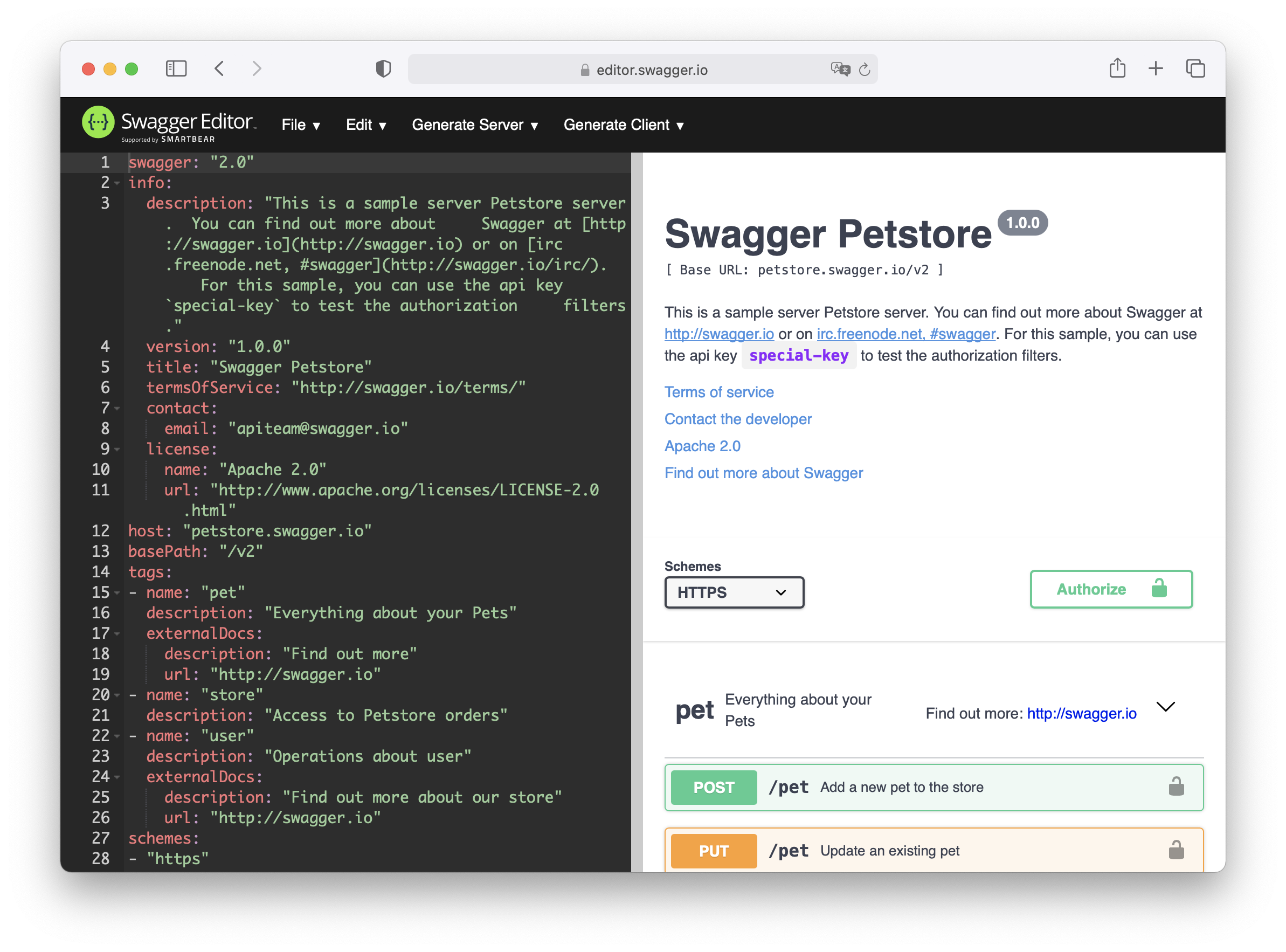

There are two ways to write OpenAPI specifications. The most straightforward approach is to write the specification manually. Coupled with OpenAPI mocking services, it’s also the fastest way to unblock your client-side developers and let them work with the API that doesn’t exist yet.

To get the feeling of how OpenAPI looks like, you can start with an online editor at editor.swagger.io.

Online swagger editor

I wouldn’t recommend using an online editor for anything serious, though. Fortunately, you can have the same functionality in your IDE or editor with an extension.

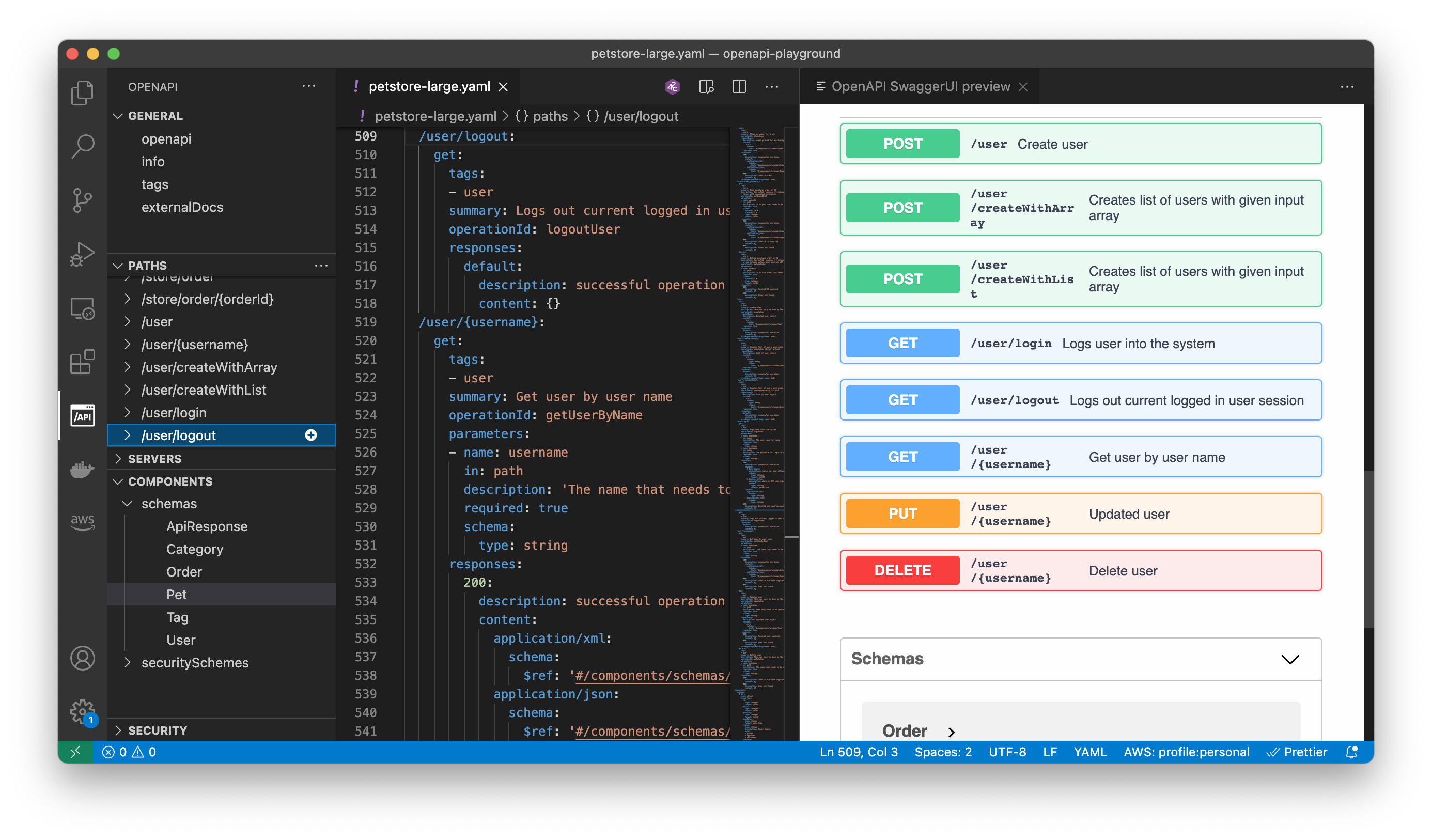

When I’m in VScode, I use an OpenAPI Editor from 42Crunch.

OpenAPI editor in VSCode

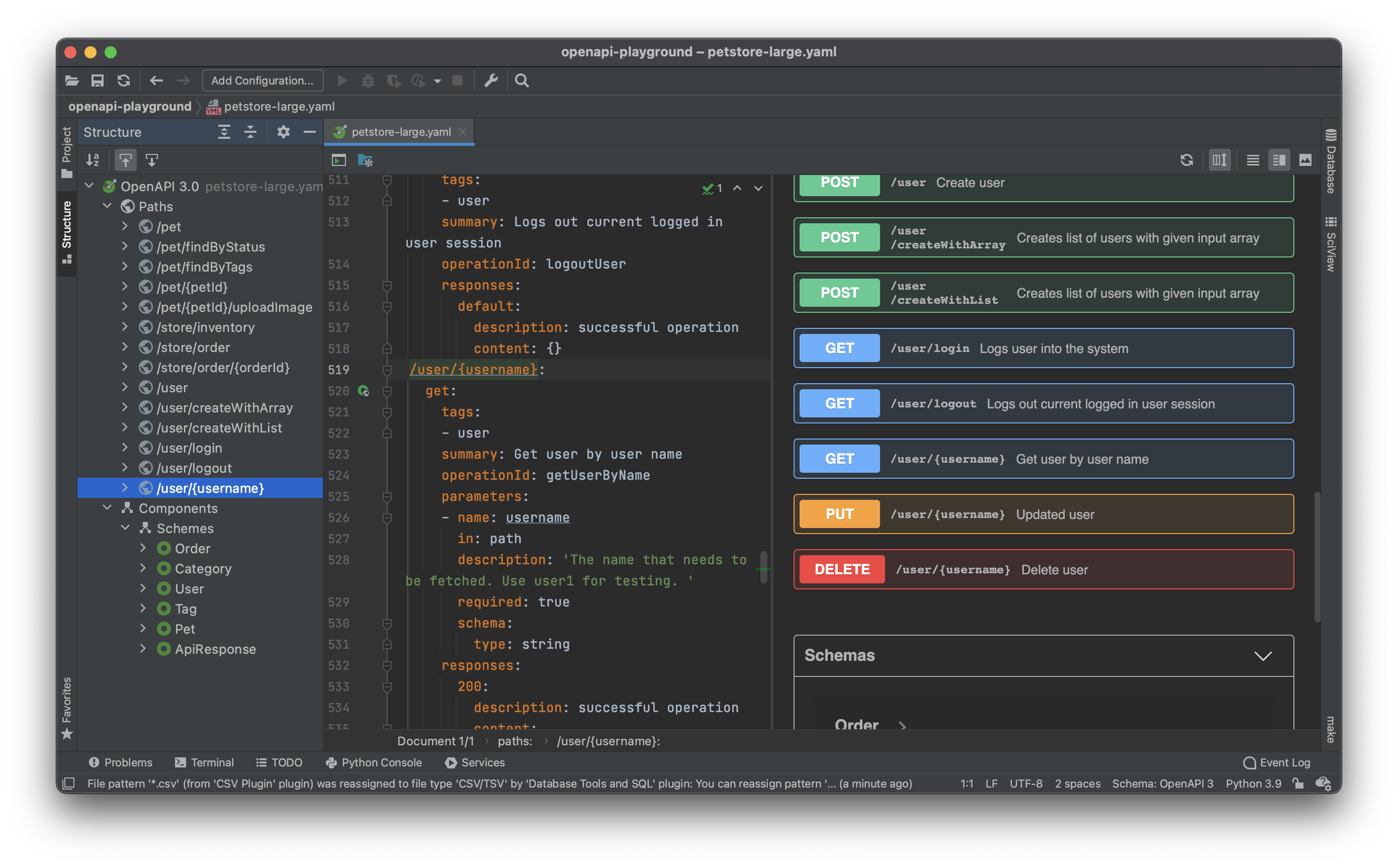

In PyCharm, I use an OpenAPI Specifications plugin from JetBrains. The plugin from 42Crunch is also available if you prefer it.

OpenAPI editor from JetBrains in PyCharm

OpenAPI renderers

OpenAPI renderers take your YAML specification and turn it into a website with nicely formatted documentation.

Swagger UI is the most popular renderer. It goes even further than generating browsable documentation and lets you play with your API right from the browser.

Swagger UI is purely client-side. It runs a JavaScript code that reads the specification from a remote URL, parses it, and converts it to the interface.

If you installed an IDE extension, you don’t need to install anything else. All extensions come with a command opening the Swagger UI right in the editor window: that’s what you’ve just seen in the previous screenshots. If you want to install it, though, you can find all the different options in their installation instructions.

If you have Docker installed locally, the easiest way to get started with a separate Swagger UI is to run it with a single command:

docker run -p 8080:8080 swaggerapi/swagger-ui

The Swagger UI will be available at http://localhost:8080.

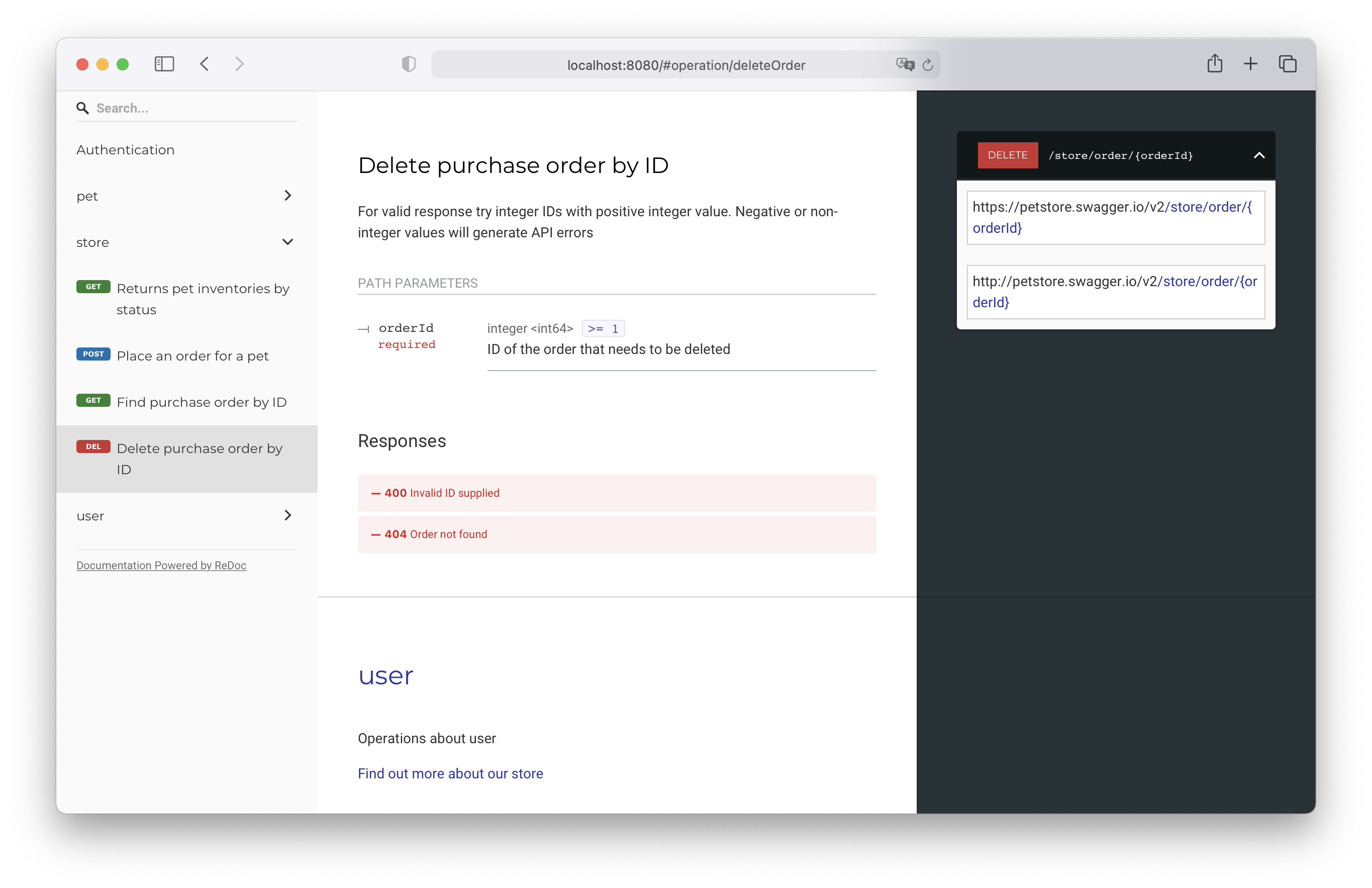

ReDoc, an alternative to Swagger UI. It has a slick three-column interface, similar to Slate. The API looks cool, but an API playground is provided only in their paid hosted version.

ReDoc supports extra fields to your attributes, so-called vendor extensions. These fields provide more options to control how to render the documentation. For example, you can add a key x-codeSamples to your request specs and provide code samples in different programming languages. If you want something similar to Slate but generated automatically, that’s probably the closest you can get.

As with Swagger UI, Docker is the fastest way to run ReDoc:

docker run -p 8080:80 redocly/redoc

ReDoc will be available at http://localhost:8080.

ReDoc serving a file from localhost

Generate OpenAPI from the code

Some frameworks can generate OpenAPI specs for you. You can stop worrying about the divergence between your specification and the implementation. The spec is built from the code, and it’s always up-to-date!

FastAPI is the framework that comes to mind first. It thinks, lives, and breathes OpenAPI and lets you express quite advanced OpenAPI constructs with Python.

Django-REST-Framework is a framework that can do everything for your API. That said, when using it, I found that if you don’t use model serializers, it’s close to impossible to write a decent API specification from the code. Eventually, I found that writing a plain YAML file from scratch was faster and easier. This way or another, here’s the schema API guide, and here’s the guideline on how to render the documentation.

apispec is not a framework, but a library that provides a Pythonic interface to OpenAPI constructs. It has multiple integrations with different tools and frameworks, including Flask, Pyramid, aiohttp, and Falcon. The list of integrations is available on the ecosystem page.

Internal documentation

What to write. While the target audience of the API documentation is client-side developers, the primary audience of the internal documentation is the developers of the service itself.

There, we outline things like installation and configuration instructions, architectural choices, or guiding principles. Internal documentation can help navigate the code, deploy things to production, add a new dependency, apply a database migration, etc.

Where to store. I prefer to keep the internal service documentation in the same repository as the service itself in a separate directory, like docs. The closer the documentation is to the code, the less the chance to get it out of sync with the implementation. Don’t overthink it. Something as simple as a bunch of markdown files in the directory can work. Other developers can browse the documentation right from their editor or use the GitHub interface.

Rendering the internal documentation

The next step in streamlining the experience with the documentation is to turn this documentation into a standalone website. Here, any static site generator can help, but the Python world provides a few “traditional” options that are best suited for documentation and integrated with other tools and services.

Sphinx is the de-facto standard in the Python world. Powerful, but a bit on the challenging side to master. That said, most projects with extensive documentation prefer Sphinx over alternatives.

MkDocs tries to make writing documentation a delightful process. Unlike Sphinx, MkDocs uses Markdown under the hood. The ecosystem of Markdown is rich and spans well beyond the scope of Python. Plugins, editors, formatters, converters, everything is at your service. MkDocs configuration is straightforward. In its simplest form, it’s a single YAML file with the project name and a list of pages.

# File mkdocs.yml

site_name: My Project

nav:

- Home: index.md

- About: about.md

My choice for Python project documentation is MkDocs with the mkdocs-material theme.

Other renderers

The beauty of internal documentation is that you’re not limited to doc-specific frameworks; you can use any static site generator. Many of them have themes specifically suitable for documentation websites. I provide below some examples.

Pelican, the #1 static site generator written in Python.

Hugo is a popular Golang-based framework for building sites. Hugo runs this blog. Documentation templates.

Docusaurus is a static site generator from Facebook. Their core focus is helping to get the documentation right and well, but they made it possible to build any website, as it is a React application.

Next.js takes another step further away from documentation / static site generators camp. It’s not quite a static site generator, but rather a fully-fledged React-based framework that happens to be able to export pages to HTML. If you are a friend of JavaScript and React, it can be an option, but it’s overkill as a starting point.

Serving the internal documentation

Anything that can serve a static website can serve your documentation. If you don’t want to make your documentation public, opt in for a solution that can make your documentation private. Below I will provide some solutions that should fit your needs.

Read the Docs is the de-facto standard for serving technical documentation, especially popular among Open Source projects. It supports Sphinx and MkDocs out of the box, supports multiple versions of the documentation and localized versions. The project readthedocs.com provides commercial support and serves both public and private documentation.

GitHub pages is the natural choice if you keep your projects and documentation on GitHub. Starting with the Pro or Team tariff plans, you can make your pages visible to your collaborators only.

Gitlab pages provides the same functionality, but unlike GitHub, private websites are available even on the free account. There is a Gitlab group pages with examples of projects sharing documentation, including mkdocs, Sphinx, among dozens of others.

netlify integrates well with CI/CD workflows and is free for public sites. The pro version lets you create password-protected sites, and the business plan provides role-based access control.

In all these cases, you build your documentation within the CI/CD pipeline and deploy static pages to the server.

My stack

To wrap up the discussion about the documentation, I will share my preferences for the stack.

- API specification format: OpenAPI.

- OpenAPI spec editor: PyCharm.

- To generate the API from the code: FastAPI.

- To render the API: Swagger UI.

- To write documentation: MkDocs.

- To serve documentation: nothing (read from the editor) or Read the Docs.

If you like it, please share it and tag me. I’m @rdotpy. If you want to discuss it, drop me a line. My DMs are open.