Python code cleanup for beginners. 12 steps to readable and maintainable code.

It’s my responsibility to hire Python developers. If you have a GitHub account, I will check it out. Everyone does it. Maybe you don’t know, but your playground project with zero stars can help you to get that job offer.

The same goes for your take-home test task. You heard this, when we meet a person for the first time, we make the first impression in 30 seconds, and this biases the rest of our judgment. I find it uncomfortably unfair that beautiful people get everything easier than the rest of us. The same bias applies to the code. You look at the project, and something immediately catches your eye. Leftovers of the old code in the repo, like leftovers of your breakfast in your beard, can ruin everything. You may not have a beard, but you get the point.

Usually, it’s easy to see when it’s a beginner’s code. Below, I provide some tricks to fool recruiters like me and increase your chances of passing to the next interview level. Don’t feel bad if you think like you’re gaming the system, because you are not. Applying these little improvements to your code not only increases your chances to succeed at the interview, but you also become a better developer. Which I can’t tell for drilling focusing on memorizing algorithms or modules of the standard library.

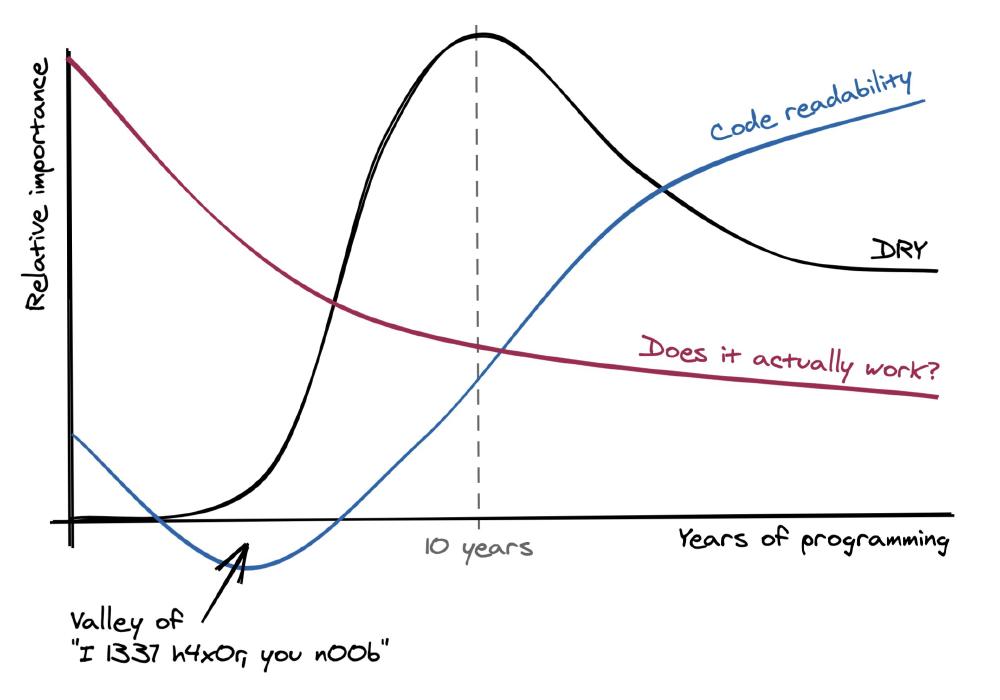

What’s the difference between a beginner and a more experienced developer? Beginners did not work with the legacy codebase, and they don’t see value in investing in a maintainable solution. Quite often, they work alone and equally, they don’t care much about the readability.

Your goal is to show that you care about the readability and maintainability of your solution.

Let’s see what we can do to improve the quality of your Python project. These tips make your code better, and if you don’t cargo-cult them, they also make you a better developer.

Step 1. Declutter the repo

Open your repo page on GitHub. Do you have .idea, .vscode, .DS_Store or *.pyc files? Have you committed your virtualenv there? Remove them now, and add files and directories to the gitignore. The rule of thumb is to avoid keeping in the codebase anything that you haven’t created yourself. There is a good tutorial from Atlassian to know more about gitignore and what to ignore in general.

A good starting point for the .gitignore. Add it to your repository in the first place.

*.pyc

*.egg-info

# If you're on Mac

.DS_Store

# If you have a habit of creating a virtual environment

# inside the project, as I do

/env

# Configuration and secrets (see an example in the next section)

/.env

For a bigger gitignore, use the one from the GitHub’s collection as a stargting point and a source of the inspiration.

Step 2. No passwords in the code

No passwords to the databases, API keys to external services, or secret keys for encryption in the repo! Move the secrets to configuration files or environment variables, or read them from the secret store, and never commit them to the codebase. The 12-factor guide is an excellent and always relevant read, and its advice about configs is on-point.

It’s a snippet from a Flask application where the author keeps the database requisites in the code. Don’t do this!

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = "postgresql://user:secret@localhost:5432/my_db"

Moving requisites to the environment is quite straightforward.

import os

from flask import Flask

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = os.getenv("SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI")

Now, before starting the application, you need to initialize the environment.

export SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI=postgresql://user:secret@localhost:5432/my_db

flask run

To avoid initializing the environment from your console, take a step further and include your requisites in a file .env. Install the package python-dotenv and initialize your environment right from the Python code.

That’s how the .env would look like

SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI=postgresql://user:secret@localhost:5432/my_db

Reading this file from your application looks like this:

import os

from dotenv import load_dotenv

from flask import Flask

load_dotenv()

app = Flask(__name__)

app.config["SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI"] = os.getenv("SQLALCHEMY_DATABASE_URI")

Don’t forget to add the path to your .env file to .gitignore so that you don’t commit it accidentally.

Step 3. Have a README

Have a top-level README with the purpose of your project, installation instructions, and the quick start guide. If you don’t know what to write there, follow the Make a README guideline.

As suggested by the “Make a README” resource, include in the README installation and usage instructions. The example below also includes contributing guidelines and a license, which is crucial for an open-source project.

# Foobar

Foobar is a Python application for dealing with word pluralization.

## Installation

Clone the repository from GitHub. Then create a virtual environment, and install all the dependencies.

```bash

git clone https://github.com/username/foobar.git

python3 -m venv env

source env/bin/activate

python -m pip install -r requirements.txt

```

## Usage

Initialize the virtual environment, and run the script

```bash

source env/bin/activate

./pluralize word

words

./pluralize goos

geese

```

## Contributing

Pull requests are welcome. For major changes, please open an issue first to discuss what you would like to change.

Please make sure to update the tests as appropriate.

## License

[MIT](https://choosealicense.com/licenses/mit/)

Step 4. If you use third-party libraries, have a requirements.txt

If your project requires third-party dependencies, declare them explicitly. The simplest way is to create a requirements.txt file in the top-level directory, one dependency per line. Don’t forget to add an instruction to use requirements.txt to the README. Read more about the file in the pip user guide

requirements.txt

gunicorn

Flask>=1.1

Flask-SQLAlchemy

psycopg2

It’s always good to have a reproducible environment. Even if a new library comes out, you keep using the old battle-tested version until you explicitly decide to upgrade the version. It’s called “dependency pinning” and the easiest way to advance with it is to use pip-tools. There, you have two files: requirements.in and requirements.txt. You never modify the latter by hand, but you commit it along with requirements.in.

Here’s the source file requirements.in:

gunicorn

Flask>=1.1

Flask-SQLAlchemy

psycopg2

To get requirements.txt you compile it by running a command pip-compile

#

# This file is autogenerated by pip-compile

# To update, run:

#

# pip-compile

#

click==7.1.2 # via flask

flask-sqlalchemy==2.4.4 # via -r requirements.in

flask==1.1.2 # via -r requirements.in, flask-sqlalchemy

gunicorn==20.0.4 # via -r requirements.in

itsdangerous==1.1.0 # via flask

jinja2==2.11.2 # via flask

markupsafe==1.1.1 # via jinja2

psycopg2==2.8.6 # via -r requirements.in

sqlalchemy==1.3.19 # via flask-sqlalchemy

werkzeug==1.0.1 # via flask

# The following packages are considered to be unsafe in a requirements file:

# setuptools

As you can see, the resulted file contains the exact versions of all the dependencies.

Step 5. Format your code with black

Inconsistent formatting doesn’t prevent your code from working. Still, formatted code makes your code easier to read and to maintain. Fortunately, code formatting can and should be automated. If you use VSCode, it suggests installing “black”, an automatic source code formatter for Python, and reformats your code on save. Also, you can install black and do the same from the console.

The code is hard to read and to extend

def pluralize ( word ):

exceptions={

"goose":'geese','phenomena' : 'phenomenon' }

if word in exceptions :

return exceptions [ word ]

return word+'s'

if __name__=='__main__' :

import sys

print ( pluralize ( sys.argv[1] ) )

Black guarantees that the code keeps the same functionality. It only saves you from the mental burden of manually following the same formatting guideline.

def pluralize(word):

exceptions = {"goose": "geese", "phenomena": "phenomenon"}

if word in exceptions:

return exceptions[word]

return word + "s"

if __name__ == "__main__":

import sys

print(pluralize(sys.argv[1]))

Step 6. Remove unused imports

Unused imports are usually left hanging in the codebase after some experiments and refactoring. If you don’t use a module anymore, don’t forget to remove it from the file. Editors usually highlight unused imports, making them an easy target.

import os

print("Hello world")

Well, that is trivial.

print("Hello world")

Step 7. Remove unused variables

The same goes for unused variables. You may have them because you followed the flow and though that a variable will be useful later on, but it turned out to be never used in the first place.

The variable “response” is not used.

def ping(word):

response = requests.get("https://example.com/ping")

def ping(word):

requests.get("https://example.com/ping")

Step 8. Follow PEP-8 naming conventions

Like formatting guidelines, not following the naming convention doesn’t make your code invalid, but makes it more difficult to follow. Besides, uniform naming frees up your mind from taking the decision every time you need to choose a name for a new object. Read PEP-8 Naming Conventions for enlightenment.

- File names and directory names: follow

lowercase_underscores - Function and variable names: follow

lowercase_underscores - Class names: follow

CamelCase - Constant names: use

UPPERCASE_UNDERSCORE

file: say_hello.py

#!/usr/bin/env python

import sys

DEFAULT_NAME = "someone" # <- UPPERCASE_UNDERSCORE

class GreetingManager: # <- CamelCase

def say_hello(self, arguments): # <- lowercase_underscores

if len(arguments) < 2:

target_name = DEFAULT_NAME

else:

target_name = arguments[1] # <- lowercase_underscores

print(f"Hello, {target_name}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

GreetingManager().say_hello(sys.argv)

Step 9. Verify your code with a linter

Linters analyze your code for some errors that can be defined automatically. It’s always a good idea to verify your code with a linter before committing the changes.

IDEs and editors such as pycharm or VSCode have built-in linters and highlight problems. It’s up to you, though, to act upon it. Look, at first, the error messages may look cryptic. Learn more about it, it’s an investment worth made.

As for the command-line linters, I would recommend flake8. It has sensible defaults, and usually, the errors it reports are worth fixing. If you want to be more strict with yourselves, you can use pylint. It detects more errors, including many of those that we haven’t touched here.

You can already notice some problems. Let’s compare the output of flake8 and pylint.

import requests

import os

def PingExample():

result = requests.get("https://example.com/ping")

flake8 ping.py

ping.py:2:1: F401 'os' imported but unused

ping.py:4:1: E302 expected 2 blank lines, found 1

ping.py:5:5: F841 local variable 'result' is assigned to but never used

pylint ping.py

************* Module ping

ping.py:1:0: C0114: Missing module docstring (missing-module-docstring)

ping.py:4:0: C0103: Function name "PingExample" doesn't conform to snake_case naming style (invalid-name)

ping.py:4:0: C0116: Missing function or method docstring (missing-function-docstring)

ping.py:5:4: W0612: Unused variable 'result' (unused-variable)

ping.py:2:0: W0611: Unused import os (unused-import)

ping.py:2:0: C0411: standard import "import os" should be placed before "import requests" (wrong-import-order)

--------------------------------------------------------------------

Your code has been rated at -5.00/10 (previous run: -5.00/10, +0.00)

Step 10. Remove debugging prints

It’s OK to debug with strategically located prints here and there. Just don’t commit them after the problem is solved.

The author wanted to see the effect of the function, storing the object in a file. The BEFORE and AFTER prints have nothing to do with the function’s purpose and clutters the output. Once they played their role, they should be removed.

def serialize(obj, filename):

print("BEFORE", os.listdir())

with open(filename, "wt") as fd:

json.dump(obj, fd)

print("AFTER", os.listdir())

We made the function smaller and more comfortable to follow, which is always a good sign.

def serialize(obj, filename):

with open(filename, "wt") as fd:

json.dump(obj, fd)

Step 11. No commented out code

Clean up your repository from your past experiments and old versions of the code. If you ever decide to get back to the old version, you can always roll back to it with your source control system. Leftovers of the old code confuse the reader and leave an impression of carelessness.

The author experimented with some ad-hoc conversions of the name. They decided not to include it to the final version but kept the results of their experiments.

name = input("What's your name: ")

#short_name = name.split()[0]

#if len(short_name) > 0:

# name = short_name

print(f"Hello, {name}")

name = input("What's your name: ")

print(f"Hello, {name}")

Step 12. Wrap your script with a function

In the beginning, your code usually follows the flow of your thoughts and contains a sequence of instructions to execute. Make it a habit to wrap this sequence to a function right from the beginning. Call this function as the last statement of your script, protected with an if __name__ == "__main__" clause. This will help you to evolve the code in a structured way by extracting some helper functions, and later on by turning the script into a module, if necessary.

The execution flow starts from the top to bottom. Easy to follow for simple scripts, but hard to evolve in a structured way.

#!/usr/bin/env python

name = input("What's your name: ")

print(f"Hello, {name}")

The execution flow starts on the last line, where we call the say_hello() function. It may look like overkill for two lines of code, but it makes the code easier to change. For example, you can already wrap your function with click for command-line options.

#!/usr/bin/env python

def say_hello():

name = input("What's your name: ")

print(f"Hello, {name}")

if __name__ == "__main__":

say_hello()

Challenge for you

Did you know that on average you retain only 10% of what you read?

Fortunately, there is a hack. Practicing results in 80% of retention of knowledge. Here is my challenge: take one of your projects and apply all twelve steps to it. It’s 8x more likely that you become a better developer.

What else to read

If you care about maintainability, read my post about data structures: Don’t let dicts spoil your code.